Hunters

When I set out for Louisiana to gather material for my next book, I decided to spend some time in the swamps with someone who had spent most of his life there. My guide was Bruce Mitchell, known as the “Alligator Man” from the TV show Swamp People. “Alligator Man” is his marketing nickname. Bruce has a very distinctive appearance. He is always dressed in denim overalls with a bandana tied around his head in the colors of the U.S. national flag. He has long gray hair and a prominent belly. In the summer, he never wears t-shirts. The jeans manufacturer that Bruce wears made a deal with him many years ago. Without those pants and the bandana, Alligator Man would be like Superman without his cape. It’s his trademark.

Bruce’s house stands in the shade of old trees, where local birds hold their daily concerts. The entire area is covered in thick green grass. It’s a charming and incredibly pleasant place to live. Before we headed out to the swamps, we sat on the porch and chatted.

“I grew up in the swamps. My grandfather used to take me there all the time. It’s my second home. I hunted there as a little boy, and I still hunt there today.”

“Where did your love for the swamps come from, Bruce?”

– “Is that why they invited you to be on the TV show?”

“Yeah, probably. They approached me. They were looking for people who were deeply rooted in the swamps. People who grew up there. For thirty years, my wife, my father-in-law, and I ran a big business, a farm with alligators and turtles. We bought and bred turtles, then exported millions of them. We also hunted alligators and bought them from other hunters. We had a large slaughterhouse where we processed them and recovered the skins. We would send up to 50 tons a year overseas. I employed 38 people. It was a big business.”

“What kind of turtles did you export? The ones with red stripes on both sides of their snouts?”

“Yeah, those.”

“We had a lot of them in Poland. There was a huge craze for them. At one point, kids went crazy for them.”

“There’s a good chance they were from me. The same craze was in many other countries around the world, but eventually it died out. When we were kids, we played with turtles, dogs, and cats. Now kids sit by the console. Why would they want a turtle?”

“How long do you have to raise an alligator before it’s ready to be killed?”

“One year.”

“Okay, they don’t need to eat much, so it’s probably profitable…”

“If you want them to grow, you have to feed them a lot,” Bruce laughed. “But you can also hunt them. That way you get fully grown ones you didn’t have to feed. You can process them for meat or sell them. In good times, I used to make up to 45 thousand dollars in 15-20 days of hunting. It was quick money.”

“Why did the prices drop?”

“Because of the farms. They bred so many of them that the price had to drop. They would go out to the swamps, collect eggs, breed the young. That killed the business.”

“When did that happen?”

“A few years ago.”

“So, the TV shows about alligator hunting are only for television purposes now? It’s no longer worth hunting?”

“Yeah, it’s not worth it.”

“Well, you killed them on camera. You could have sold them. What’s the price now?”

“Five dollars for a 2-meter alligator. Half of that price goes to the landowner where you’re hunting. You get 2.5 dollars in your pocket. From that, you have to pay for fuel, spend time. The hook and the line are worth more than the alligator,” Bruce chuckled.

“Why are alligator leather shoes, wallets, and watch straps still so expensive, if they’re paying 5 dollars for the whole animal, and why didn’t you start such a business yourself? The margin seems enormous.”

“Yeah, those products hold their value. The problem is tanning alligator leather. Nobody does it here. You have to send it overseas. It’s been a secret for centuries—how to tan the hides properly. They never do the whole process in one place so people don’t learn the technology. Some of the work is done here, but the main process happens in France.”

“In France? But they don’t have alligators there.”

“Yes, in France. They also do it in a few other places around the world, but the ones from France are the best quality.”

“How do you catch alligators in the swamps?”

“You stretch a line across a canal. You hang hooks on it, and put chickens on them. Then you come back after a few hours or days and collect them from the hooks. Most are still alive, so you have to shoot them. You can also shoot them from a boat, but that’s risky because a shot alligator might go under the water and be hard to find. We avoid hunting females.”

“How do you recognize them?”

“They have babies with them or stay near their nest.”

“Do you always take a gun into the swamps? Do you always carry a gun with you?”

“Always. That’s how I was raised. I grew up in the woods, in the swamps. The first thing I pick up when I get out of bed is my knife and gun.”

“In my world, no one thinks like that.”

“It’s different here. You grow up with a gun. Owning one is natural.”

Bruce stood up from the table, reached into his overalls pocket, and placed a knife, a small folding pistol, and a fire starter on the table.

“These three things are always with me,” he said.

“What’s that little thing? For snakes?” I pointed to the pistol.

“You can shoot an alligator with it too. It’s very small, foldable, and fits easily in my pocket. Perfect for me. I haven’t used it in a while, but the hunting season starts in September. For years, the swamp kept us. Not only did it feed us, but it also made us money. We hunted not only alligators but also nutria. We hunted them, skinned them, and sent them to Russia. Unfortunately, that business ended too. In 2008, when the global financial crisis hit, it ended. Before that, we could get up to 15 dollars for a fur. There are millions of them here. It was a good business. You could catch 200 or 300 a day. Imagine how much money that is.”

“How do you catch that many in one day?”

“You shoot them. They’re everywhere. But forget about that now. The fashion for real furs has passed. Back in the day, you could go to the swamps and bring back a lot of stuff to sell. That’s how I grew up. Until I was about forty, we hunted, fished for crawfish, frogs, fish, shrimp, crabs, tracked animals, set traps. Every month, it was something different. That’s how entire families made a living. Now, it’s gone. I’m probably the last generation that remembers that way of life. It’s over. There’s no money in it anymore.”

“So, what still makes sense?”

“Crawfish. There’s a big demand locally and among tourists. People love Cajun cuisine, Louisiana culture. They want traditional dishes. Crawfish, sausage, corn—that’s the foundation.”

“Crawfish are everywhere, but not everywhere can you catch them. Who owns the swamps? Those are huge areas…”

“Right now, most of it belongs to the state. A hundred years ago, the rich and banks bought up large tracts of swamp land. They bought it for pennies, then started cutting down trees. After they cleared the land, they brought in oil companies. Wells were drilled in the swamps. People got rich selling oil. They also leased land to hunters and trappers, but as you know, that stopped being profitable. I’m talking about hunting. So, there are no more land lease takers. You have to pay taxes on the land, so it became a problem. People had large tracts with a few wells on them, but the rest of the land sat idle and generated costs. Louisiana introduced a law where if you give the land to the state, you still keep the rights to the oil under it. People offloaded the tax burdens, still earn from the oil, and the state got the land back.”

After more than an hour of conversation, we decided to head into the swamps. We jumped into Bruce’s twenty-year-old truck, pulling a trailer with a boat. This truck had seen many hunts, I thought. Outside, as always, it was raining. Suddenly, Bruce blurted out, as if reading my mind:

“You know our saying here? ‘You will definitely get wet because you don’t sweat.’ In loose translation: ‘You’ll get wet for sure, because you’re not sweating.’ In other words, in Louisiana, you’re always wet, either because of the heat or the rain. You can’t win with it.”

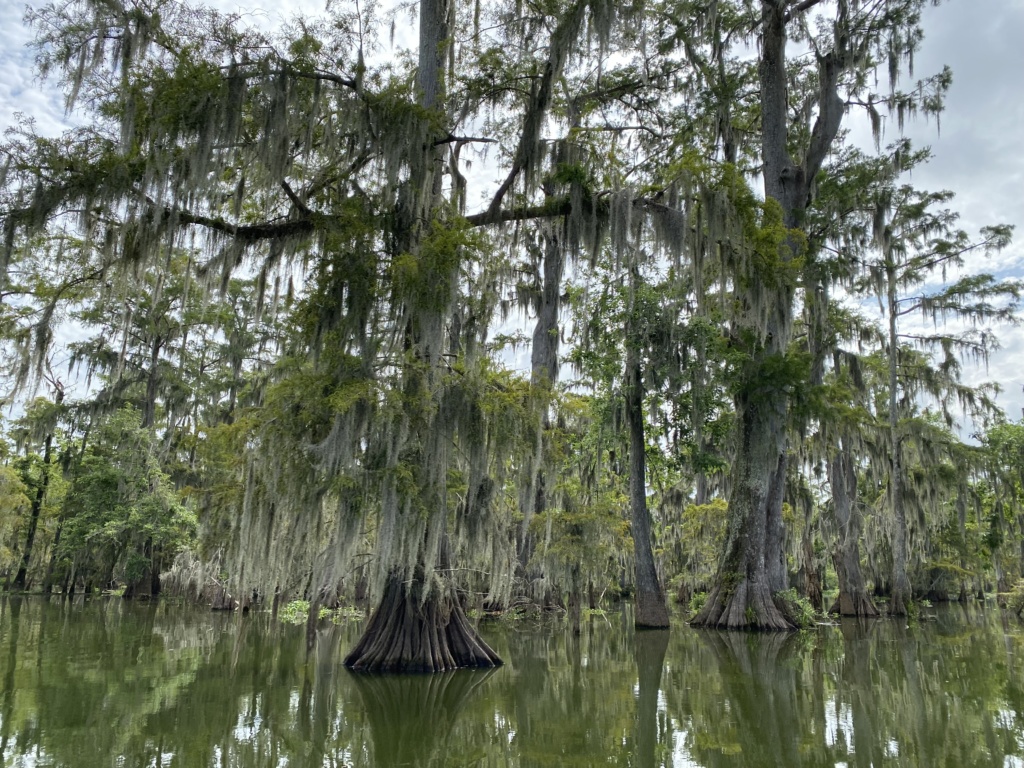

We launched the boat and set off. The sky looked like it did in November in Poland—gloomy, gray, but definitely not stormy. It was warm, raining, and we were drifting through various channels. Bruce was driving fast. The wind whipped the rain at us, and the sound of the engine made it hard to talk. It grew colder. I grabbed a black trash bag from the bottom of the boat, cut a hole for my head and arms, and had a makeshift rain jacket. Dry and warm. Bruce smiled. He was still standing there shirtless in his overalls, steering the boat. He looked as if the cold and rain didn’t bother him. His long gray hair, sticking out from under his bandana, waved behind him as he stood like a statue, only occasionally sighing. His mood had definitely changed. It had gotten cold and wet. The rain lashed at our skin. It was getting miserable. He had to slow down for it to be bearable. Finally, he pulled up to the shore, and we hid in the reeds. I thought it was just a stop to wait it out, but among the growing “sawgrass” in the water, I noticed a small plastic pipe sticking out of the water with water flowing from it. Before I could ask, Bruce explained:

“Look, here’s fresh water from a deep well. When I was a kid, there was a settlement here, and they got their water from this source. This well is over a hundred years old. Recently, someone replaced the pipe. The locals know these spots and don’t take care of them. I remember, 40 years ago, we’d come here with glass milk bottles or jars and fill them with water. Back then, we didn’t have plastic. It’s been flowing here for over 100 years. Not many people know about it. The old timers remember. It’s handy to know when you forget to bring water from the city.”

The weather was becoming increasingly unbearable. The wind picked up, and the rain grew stronger. In the distance, lightning struck.

I looked at Bruce, but he didn’t let on that it had affected him. Tough guys don’t crack, but idiots die, I thought. Finally, I asked:

“Do you often end up in the swamps during a storm?”

“Don’t worry, very often.”

Fear was not an option. Fear paralyzes and doesn’t help at all. Nature invented it so we would avoid danger and make a run for it. In this situation, I calmly assessed the situation and thought we should get off the water. When you’re not steering and you’re relying on a guy who has spent his whole life here, you have little to say. However, you can count on his rationality. In these situations, the problem is the “showing off” of someone who wants to prove they’re a seasoned sea dog in the middle of the ocean. We were sitting in an aluminum boat in the middle of a swamp that stretched for miles. As far as the eye could see, there were tall cattails and occasionally low trees. So, we were the “highest point” in a radius of several hundred meters, and that too, was metal, in the middle of the water. We moved slowly forward. Conversation was no longer possible. Water poured from the sky in torrents. Visibility had dropped to just a few dozen meters. The wind was so strong that it felt like the rain was falling not from the sky, but parallel to the water’s surface. My colorful umbrella, retrieved from the water, was useless. I threw it under the bench I was sitting on to keep it from being blown back into the water. However, the trash bag worked great. The raindrops bounced off it, and despite the downpour, my t-shirt remained dry. Bruce had no protection. The rain mercilessly lashed his body. He had to stand to see where we were going. In a word, his mood had soured. In the course of 10 minutes, two lightning strikes hit. It had become dreadful. I sat in silence, knowing we weren’t just drifting aimlessly. There had to be a plan, and Bruce didn’t need to explain it to me. In one of the channels, there was a wooden dock on the shore. It led to a pen for hunting dogs. The roof was made of corrugated metal, the walls were metal mesh, and there were wooden posts supporting the structure. Inside, there was a wooden floor and benches for the dogs. The only safe part of the structure during the storm. The “walls” were separated from the swamp by laying sheets of metal along them. This was to keep fewer snakes and rodents inside. It was a temporary solution because, over a meter high, in one of the mesh holes, a fresh snake skin was hanging. Inside, large wooden benches were left for the dogs to sleep on. One of them served as our seating. The storm had fully unleashed. The heavy rain struck the corrugated metal roof, the roof of our shelter, so violently that to talk, we had to shout over the deafening noise. Behind the dock where we had tied the boat, there was a large alligator, about three meters long, lying in the water. Most of its snout was above the water. It lay motionless, as if enjoying the rain. Every now and then, we heard the thunder of lightning. I took out some chocolate bars I had packed for situations like this and offered one to Bruce. We sat comfortably with a view of the water on one side and the cattails stretching to the horizon on the other, chatting to pass the time.

“Look, Bruce—a shed skin. What kind of snake is that?”

“Moccasin.”

“Has it ever bitten you?”

“Yeah, last year. My wife and I were at home because I had Covid, but I thought I was going to go crazy from boredom, so I worked a lot around the house. I said I had to take care of this damn illness—I mean, the disease,” he smiled. “I went behind the house to cut some trees, and a copperhead moccasin bit me. Understand? Sick with Covid, chopping wood, Bruce Mitchel bitten by a moccasin, right under his own house…”

“Did you go to the hospital?”

“No, they’re venomous, but not deadly. I felt terrible from the coronavirus. After the bite, I felt even worse. It burned like hell where I was bitten, but I didn’t go to the hospital. Eventually, it passed.”

Ninety percent of people would have made a different decision, but as it turned out, it worked out for him. The pen we had taken shelter in could have housed up to a dozen dogs. Inside the structure, people had left small chairs for hunters. This place served us like an abandoned cabin in the mountains during a snowstorm. The only difference was that here, it smelled mercilessly of snakes and rodent droppings.

“When are there dogs in these pens, Bruce?”

– Fear was not an option. Fear paralyzes and doesn’t help at all. Nature invented it so we would avoid danger and make a run for it. In this situation, I calmly assessed the situation and thought we should get off the water. When you’re not steering and you’re relying on a guy who has spent his whole life here, you have little to say. However, you can count on his rationality. In these situations, the problem is the “showing off” of someone who wants to prove they’re a seasoned sea dog in the middle of the ocean. We were sitting in an aluminum boat in the middle of a swamp that stretched for miles. As far as the eye could see, there were tall cattails and occasionally low trees. So, we were the “highest point” in a radius of several hundred meters, and that too, was metal, in the middle of the water. We moved slowly forward. Conversation was no longer possible. Water poured from the sky in torrents. Visibility had dropped to just a few dozen meters. The wind was so strong that it felt like the rain was falling not from the sky, but parallel to the water’s surface. My colorful umbrella, retrieved from the water, was useless. I threw it under the bench I was sitting on to keep it from being blown back into the water. However, the trash bag worked great. The raindrops bounced off it, and despite the downpour, my t-shirt remained dry. Bruce had no protection. The rain mercilessly lashed his body. He had to stand to see where we were going. In a word, his mood had soured. In the course of 10 minutes, two lightning strikes hit. It had become dreadful. I sat in silence, knowing we weren’t just drifting aimlessly. There had to be a plan, and Bruce didn’t need to explain it to me. In one of the channels, there was a wooden dock on the shore. It led to a pen for hunting dogs. The roof was made of corrugated metal, the walls were metal mesh, and there were wooden posts supporting the structure. Inside, there was a wooden floor and benches for the dogs. The only safe part of the structure during the storm. The “walls” were separated from the swamp by laying sheets of metal along them. This was to keep fewer snakes and rodents inside. It was a temporary solution because, over a meter high, in one of the mesh holes, a fresh snake skin was hanging. Inside, large wooden benches were left for the dogs to sleep on. One of them served as our seating. The storm had fully unleashed. The heavy rain struck the corrugated metal roof, the roof of our shelter, so violently that to talk, we had to shout over the deafening noise. Behind the dock where we had tied the boat, there was a large alligator, about three meters long, lying in the water. Most of its snout was above the water. It lay motionless, as if enjoying the rain. Every now and then, we heard the thunder of lightning. I took out some chocolate bars I had packed for situations like this and offered one to Bruce. We sat comfortably with a view of the water on one side and the cattails stretching to the horizon on the other, chatting to pass the time.

“Look, Bruce—a shed skin. What kind of snake is that?”

“Moccasin.”

“Has it ever bitten you?”

“Yeah, last year. My wife and I were at home because I had Covid, but I thought I was going to go crazy from boredom, so I worked a lot around the house. I said I had to take care of this damn illness—I mean, the disease,” he smiled. “I went behind the house to cut some trees, and a copperhead moccasin bit me. Understand? Sick with Covid, chopping wood, Bruce Mitchel bitten by a moccasin, right under his own house…”

“Did you go to the hospital?”

“No, they’re venomous, but not deadly. I felt terrible from the coronavirus. After the bite, I felt even worse. It burned like hell where I was bitten, but I didn’t go to the hospital. Eventually, it passed.”

Ninety percent of people would have made a different decision, but as it turned out, it worked out for him. The pen we had taken shelter in could have housed up to a dozen dogs. Inside the structure, people had left small chairs for hunters. This place served us like an abandoned cabin in the mountains during a snowstorm. The only difference was that here, it smelled mercilessly of snakes and rodent droppings.

“When are there dogs in these pens, Bruce?”

Powiedziałeś(-aś):

Usunięto treść

Ta treść może naruszać nasze zasady użytkowania.

ChatGPT powiedział:

ChatGPT

During deer hunting season, hunters bring them here. They sit on these chairs and drink bourbon while the dogs run into the swamps. These are smart dogs; they know where they can go and where they’ll fall into the water. They track deer, wild boars, deer, lynx—everything. The hunters wait. When they hear the dogs barking, they head out. Sometimes the dogs surround the prey and wait, other times they attack on their own and kill, for example, a deer. These pens are for feeding the dogs, giving them water, and providing them with a place to sleep. Sometimes the dogs get lost. They’re gone for entire days. When I’m out paddling around and see a dog on the shore, I put it on the boat and bring it here or to another pen. Eventually, the owner will come and pick it up. It’s an unwritten rule here to take the dogs and bring them back to the pens. Sometimes, when I’m tired of people and the world, I take my kayak, gun, food, and maybe a blanket, and sleep here. I’ve stayed here more than once. It’s like a local shelter. Better than a tent, and you don’t break into anyone’s house. I rest here. I relax, calm down, and escape from the world.

- I understand you, but looking at this mesh and roof, this doesn’t seem like the best place to hide from a storm.

- It’s not. I’ve had a few lightning incidents in my life. My father told me that when he was a kid, lightning killed his two friends, twin brothers, in a field nearby. They were picking cucumbers when it struck. They didn’t stand a chance.

Exactly at that moment, I glanced to the right at the alligator lying in the water. About 30 meters behind it, a lightning bolt struck. The impact was so powerful that my ears rang. Bruce fell silent, and so did I. It was close—less than 100 meters. It hit the flat area behind the canal, on the other shore. We were lucky. We looked at each other and smiled. In situations like this, there’s nothing to say. It was really close, and I got chills down my spine. After about a minute of silence, Bruce spoke up.

- One time we were feeding alligators in a pond. A storm came. The lightning was striking far off, so we just stood there and did our thing. Suddenly, it struck. Man, you should have seen it. The electricity traveled all over the fence around us. It all started glowing, and we stood in the middle watching the show. You don’t have to be afraid of rain. The alligators are in the water, and we’re on the surface. We watch out for snakes. If needed, you have your gun with you, but there’s nothing we can do about lightning. The chance of it hitting next to us again is small, so we just wait. What’s done is done. Now we wait for it to end.

- Exactly.

We stayed sitting, trapped in this metal cage. The sky was gray, like on a cloudy day. It wasn’t the usual navy-black color you often get during a storm in Poland. It was monotonous, just overcast. Finally, after 10 minutes, the rain stopped. Sometimes, in the distance, we still heard thunder strikes, so we decided to wait a little longer.

I always sign papers saying everything goes to processing. Nothing goes to waste, so it’s all good.

Have you ever hunted with your own dogs? Did you keep them in this pen?

Not with my own, but I’ve accompanied hunters.

Do you have a wild boar problem here? It’s a plague in Texas. They destroy everything, and their population keeps growing.

It’s the same here. I’ll tell you a story from a few years ago. The director of Swamp People once suggested we make an episode about hunting wild boars. We went into the woods. We parked the pickup truck next to a clearing, and I jumped into the bed. The director and the cameraman got set up for filming. I had two shotguns and 30 rounds. Both were loaded. The herd was several dozen meters away. I shot the one farthest from me, on the right side of the group, and the second one, which was just next to it. I hit both. The herd started running to the left, so I aimed at the one running first. I hit that one too. The others behind it turned back and crashed into those that were further back. It turned into chaos—boars trampling over each other—and I had time. I hit another dozen or so. When I was done shooting, satisfied, I put the gun down and looked at the director. He was furious, frothing at the mouth, with a red face from anger, glaring at me with eyes full of fury, and yelled, “What the hell did you do? I can’t show this on TV. This is a damn massacre, not a hunt…”

Well, he had a point, Bruce… – I smiled, but he continued.

The next day we did the same thing in a different spot. I stood in the truck bed again, the crew got ready to film, and I started shooting. This time, they gave me 5 rounds. With the last, fifth shot, I hit two. I killed six wild boars. I put the gun down, looked at the director, and he said, “You had to show off, didn’t you…”

What happens to the meat of the animals you kill while filming the shows?

Finally, the storm stopped. Or at least, that’s what we thought. We left the pen, wiped the benches on the boat, and set off again. The sky was still gray, looking calm. There was no wind or rain. The calm after the storm. We slowly glided down the canal and began talking. We covered a few hundred meters, and suddenly, a lightning bolt struck. This time, about half a kilometer away from us.

“What the…?” I blurted out involuntarily, and I saw the same surprise on Bruce’s face that I felt from my own words.

- “Alright, let’s turn back,” Bruce said seriously, “I don’t know where this came from, but this is starting to not be funny.”

We paddled for another 40 minutes to the place where we left the car. It was cold, but it wasn’t raining. Occasionally, a lightning bolt struck in the distance. After another strike, Bruce casually asked:

- “Do we wait on the shore, or keep going?” he asked me. “I don’t want CNN to report tomorrow that Bruce Mitchell and a writer from Poland were killed by a lightning strike.”

- “I don’t know, Bruce. There’s no shore. We can shelter in the reeds, but we’ll still be on this metal boat. We don’t have a choice, we have to keep going.”

Bruce’s question was rhetorical. He knew very well we didn’t have a choice. In situations like this, people lose the need for conversation. There’s nothing to do but trust in the outcome and keep going toward the goal. When we finally saw the parking lot, it felt safer, but we still couldn’t be sure we’d make it. Eventually, we reached the shore. I stayed by the water, holding the boat on a line, while Bruce went to get the car. We made it. We wouldn’t be in CNN, I thought—thank goodness.

On our way back from the swamp, we saw a large blue plastic bag by the highway. It was stuffed with something inside, lying right by the right lane.

Bruce pointed to it and joked:

- “Remember, never open a bag you find by the road in Louisiana.”

- “Why?”

- “You never know what’s inside…” he started laughing loudly. “It’s really easy to get rid of a body here. The alligators take care of things quickly.”

I started laughing too, and before we got home, I began to regret that our adventure was coming to an end. Bruce is a fantastic storyteller. He’s intelligent and open. I really liked him. He’s a tough guy who can survive in any situation and who likes people. At the end of our trip, I asked him one last question:

- “How would you describe the swamps in one word, Bruce?”

- “Paradise.”

- “Paradise?”

- “Yeah, it’s paradise. Out there, a person has everything they need to survive. That’s where I grew up, the swamps are my home.”